When you read Heart Lamp, it is tempting to isolate the Muslim woman’s struggle as an “othered” reality, thereby preserving a safe distance. But this collection of 12 stories gently yet firmly dismantles that illusion. Yes, it speaks in the dialects of Muslim domestic life – its rituals, gendered codes, and food – but what emerges is not a “Muslim” tragedy. It is a feminist one. An economic one. An unmistakably Indian one.

As with all patriarchal systems, men here often find validation for their failures in scripture, using religious authority to exploit the women in their lives. Themes like polygamy or lack of family planning, stereotypically attributed to the Muslim community do appear. But Banu’s true concern lies in the daughter’s right to inheritance, the widow’s invisible labour, the betrayal by one’s maternal family, and the class fractures that cut across both communities and families. Thus the Muslim woman is not singled out here, she is placed in a larger narrative of gendered erasure that spans castes, faiths, and regions.

Banu Mushtaq’s storytelling is itself radical, which makes these otherwise known stories be recognised for its literary brilliance. There are no dramatic confrontations or clear moral judgments. Her stories rest on silence that maintains the distance between observer and observed, who form dual protagonists. They orbit each other in emotional solitude, bound by unspoken assumptions and speculative empathy. The gap is maintained by religious dogma and social codes, creates an unresolved tension that the writer does not resolve. But the anxiety this generates compels the reader to lean in, to take responsibility of knowing and to painfully bear witness.

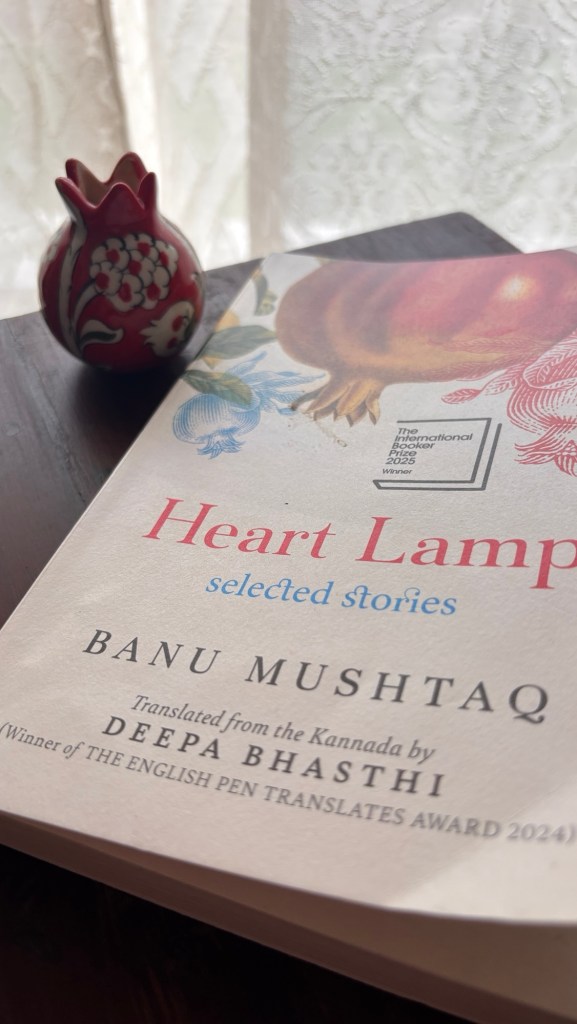

And then there is the third figure, often silent, yet emotionally visible. For me, among the many, it is the eldest daughter for whom my heart bleeds like a ripped open pomegranate fruit that’s just ripped. This eldest daughter, not yet a woman, no longer a child, becomes her mother’s quietest strength, her witness and aid. And in doing so, she vanishes. She consents to her own oblivion not from weakness, but from an instinctive understanding of her mother’s burden. It is not simply victimhood. It is brutal, inherited survival. And paradoxically, it is also the most profound form of sisterhood.

Banu does not romanticize them. She allows these girls and women to exist – undramatic yet unforgettable. That restraint is her power. And from one such story comes the name of the book as well.

While Deepa Bhasthi’s translation matches this subtle power with clarity and sensitive care. Her refusal to italicize Kannada and Urdu words is an assertion. In a publishing world that often “others” vernacular language, Deepa insists that Indian English, particularly Kannada-inflected English, is not derivative. It is a living, evolving tongue that absorbs region and culture without apology. It does not explain itself to the global reader but invites the global reader to listen, and learn.

That the Booker Prize recognised Heart Lamp is not only a literary honour, it is a political act. At a time of growing cultural dogma, linguistic purity, and state-favoured journalism, this book is both soft and subversive. It reminds us that literature does not need spectacle to be searing. That silence can be its own form of rebellion. And that the most radical stories are sometimes the ones that simply ask to be seen without theatrics.

To read this book is to sit with discomfort. And in an age that promotes noise, to sit quietly and bear witness may be the hardest but also the most necessary thing to do, before we act – act with morality

Rightly understood

LikeLike