The film Dhurandhar has occupied public discourse for some time now, with its intentionality being debated. Much of the criticism centres on the charge that it feeds a jingoistic nationalism, made persuasive because of how spectacular its craft is.

But whether a film like Dhurandhar exists or not does not matter much to me.

What matters to me is that a film like Bison exists.

A Tamil, critically acclaimed film released a few months before the Hindi blockbuster; I watched Bison around the same time I was coming to the end of ‘The Undying Light’, the personal memoir of Gopalkrishna Gandhi. Together, the film and the book offered me a moral imagination that feels especially precious at a time when not just India, but the world, appears increasingly fractured.

Bison, directed by Mari Selvaraj, is set in a small Tamil village trapped in cyclical violence between two rival feudal groups. Here, bloodshed is something unborn children are guaranteed. From this landscape emerges Kittan, an Arjuna Award winning kabaddi player whose journey is loosely inspired by real events.

Selvaraj’s brilliance lies not merely in his craft, but in the moral question that runs through much of his work, where violence, often brutal and unflinching, is central, “What does redemption look like in a society structured around inherited violence?”. And he also answers it. Answers it most, most beautifully.

As the narrative in Bison unfolds, the two feudal leaders, men directly responsible for sustaining the cycle that has consumed generations, recognise something unprecedented. Kittan represents not a tempting scapegoat…an inconsequential scapegoat, over the rival faction; but an exit from the loop itself to both the leaders. In supporting his pursuit of becoming a national-level kabaddi player, they do not suddenly transform into ‘moral’ heroes. They remain heroes who are expected to be violent. Yet they choose, briefly but decisively, to break the cycle. They enable a future that does not directly benefit their own power, not just for Kittan but for the village at large.

This choice, made against the expectations of their bloodthirsty loyalists, is not framed as repentance. Selvaraj’s storytelling anchors it instead in purpose. These men once picked up the sickle not out of an innate thirst for blood, but to secure dignity, livelihood, and possibility for their community. Their tragedy lies in how far they have drifted from that purpose. In enabling Kittan, they momentarily realign themselves with it. The film does not absolve them, but it suggests that perhaps we are not all irredeemably cruel by nature?

Reading The Undying Light alongside this made the parallel unavoidable.

Gopalkrishna Gandhi’s memoir is not a nostalgic account of India’s moral past, nor a utopian vision of its future. It is an administrative and political archive, deeply unsentimental in tone. As the grandson of Mahatma Gandhi and C. Rajagopalachari, he could easily have leaned into inherited idealism. Instead, he writes from the vantage point of institutions he served within, bringing into sharp focus the moral and constitutional importance of the President’s and Governor’s offices, as well as the delicate architecture of India’s diplomatic relationships.

While the scope of the book is panoramic, weaving in India’s political evolution, its foreign policy, and even the parallel growth of Indian arts, what stayed with me most was one persistent theme. The many internal fragilities and failures of India that long predate Independence.

Gopalkrishna Gandhi records violence relentlessly.

Political riots, caste atrocities, communal killings, and everyday brutality that rarely makes headlines. He dismantles the comforting myth of India as an inherently tolerant civilisation. The paradox he returns to repeatedly is stark. A nation that celebrates non-violence as its founding ethic continues to live with violence as its most enduring inheritance.

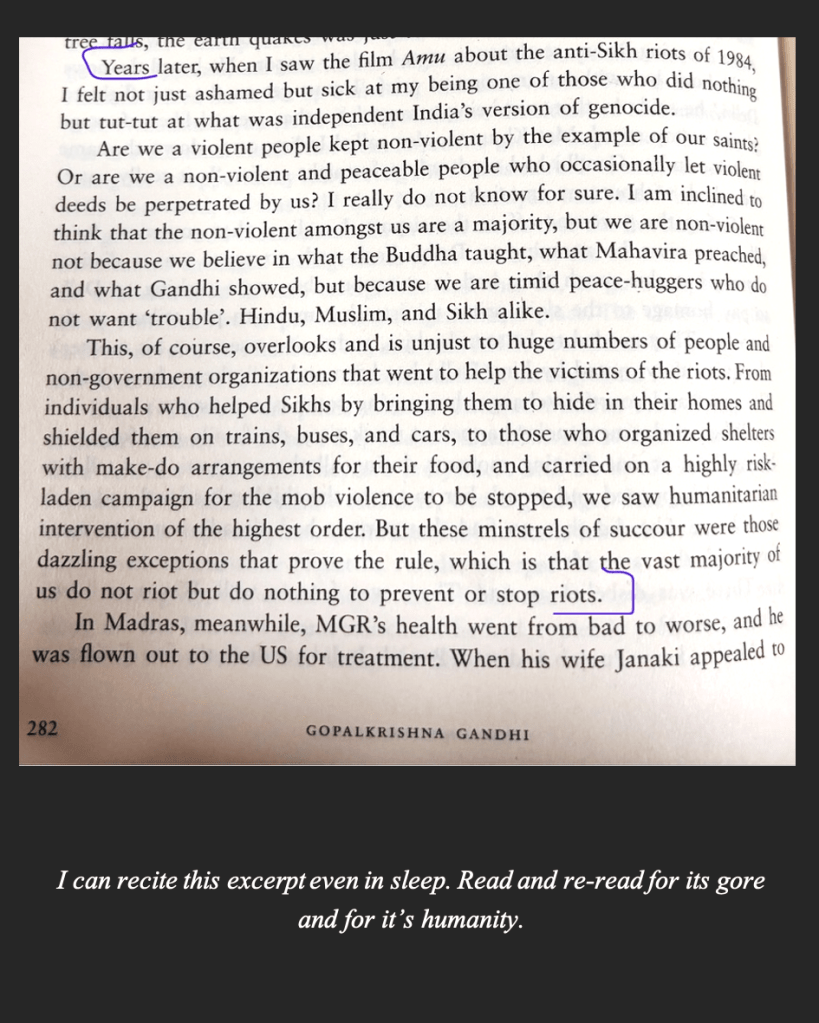

In a passage I have memorised (which is attached before this section), G. Gandhi admits that he does not believe India is tolerant in practice. What prevents constant civil collapse, he suggests, is not moral superiority but fear, inertia, and mutual vulnerability. It is cowardice, not compassion!

Yet this admission does not weaken his faith in India, as he immediately clarifies on what gives him faith, and that is precisely why the book matters.

Watching Bison, this thought acquired a strong tangent. Both the film and the memoir reject the fantasy of moral purity. Neither denies blood, guilt, or historical damage. What they insist on instead is accountability at moments of power. Redemption is not imagined as innocence regained, but as responsibility accepted.

If India has a future worth defending, it will not be defended by louder nationalism or better produced myths. It will be defended in rare moments when those with power choose restraint over applause, and responsibility over revenge. These moments will never trend, never unify a crowd, and never feel triumphant. They are small, easily missed, and morally inconvenient.

That is why Gopalkrishna Gandhi’s The Undying Light matters. The light he writes about is not a blaze of virtue or a claim of moral exceptionalism. It is a small, persistent illumination that survives not because it overwhelms the darkness, but because it refuses to be extinguished by it. Bison also gestures toward the same idea. In a landscape soaked in blood, the light does not arrive as salvation, only as a brief interruption.

Everything else, no matter how polished or popular, merely teaches us how to live more comfortably with violence. The undying light, if it exists at all, exists only in those moments when power pauses long enough to remember what it was meant to protect.