Shame is an integral foundation of Indian culture, now given a sophisticated, modern upgrade in its nomenclature – gaslighting. This new lexicon disguises the methods by which we shame, making the emotional and psychological damage deeper.

For the Indian woman, this initiation into shame often begins with the mother, patriarchy’s most complex tool. It’s a dynamic Arundhati Roy captures accurately while describing her mother as both her shelter and her storm – a duality that extends to all with only the degrees of it changing, across generations.

For the few women who have dared to shift this axis, to be more shelter than storm – the cost is immense. We celebrate them as “glass ceiling breakers,” yet rarely acknowledge their bruised and bloodied fists. We conveniently erase the trauma of being called “shameless.”

In this light, the euphoric celebration of India’s historic win against Australia in the Women’s World Cup Semi-Final on October 30th is a nauseating hypocrisy. Jemimah Rodrigues, who proved that statistics are no match for courage and faith – was until recently, trolled and abused online for her previous performances. The crowd that vilified her now exalts her.

When our women’s team falters, or women anywhere do fail; we seldom ask hard questions about institutions or investment. The outrage turns personal. Trolls attack individuals while systems escape scrutiny. This malice doesn’t just thrive in social media comments; it lives quietly within our personal WhatsApp groups and casual conversations. Silence in these spaces is complicity. If we haven’t defended these women, we have participated in their shaming.

What women achieve is not because of the system, but in spite of it. Whatever we talk about representation that exists, is only because of the “bad girls” who wear “shamelessness” like armour and bulldoze through barriers. It is tragic when the “good girls” are co-opted by patriarchy – as our mothers were/ are and somewhere we still are – to wield shame against the next generation of girls.

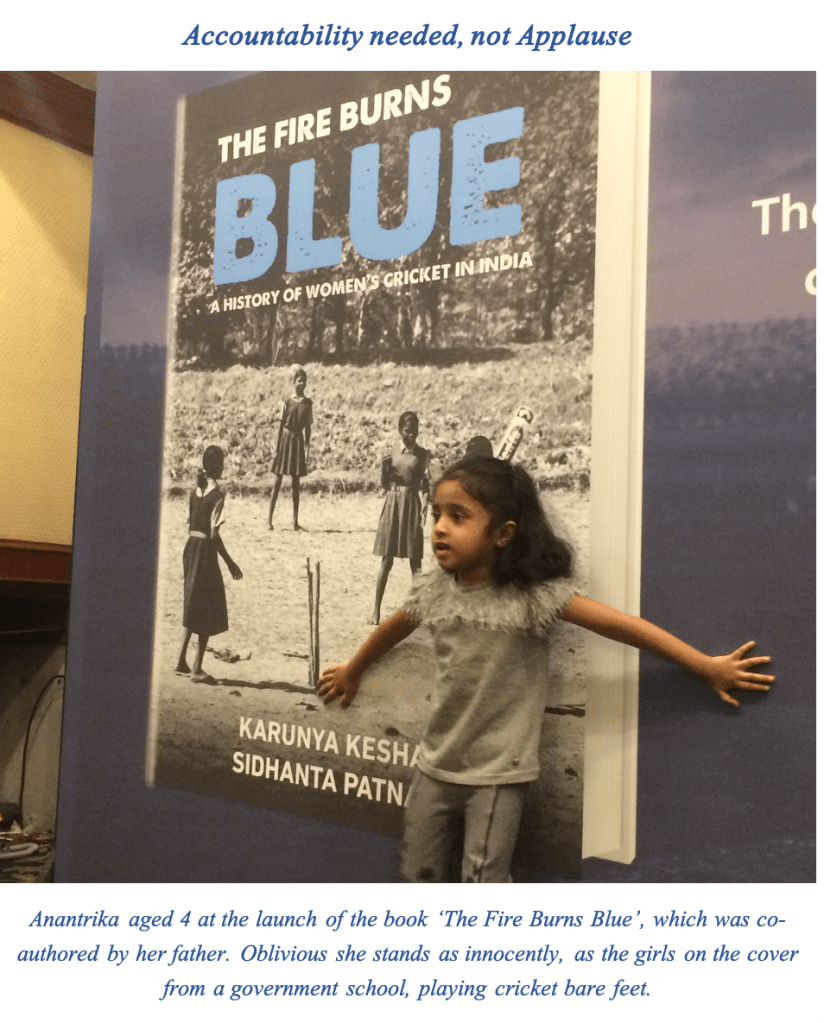

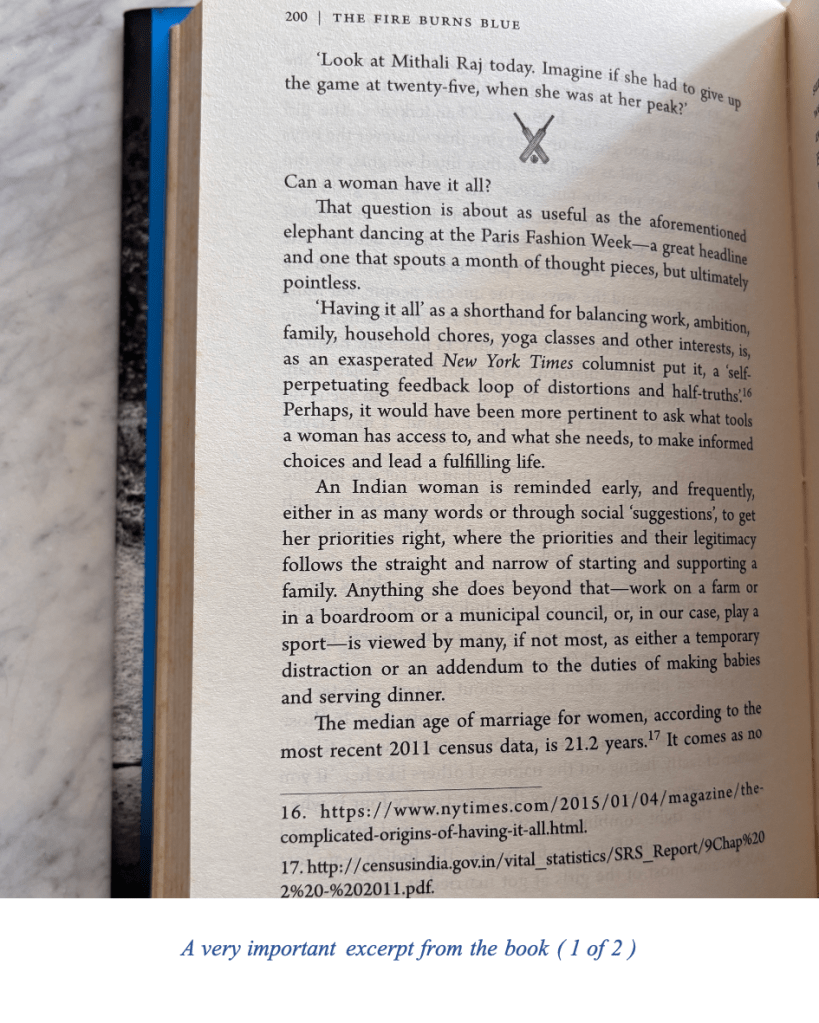

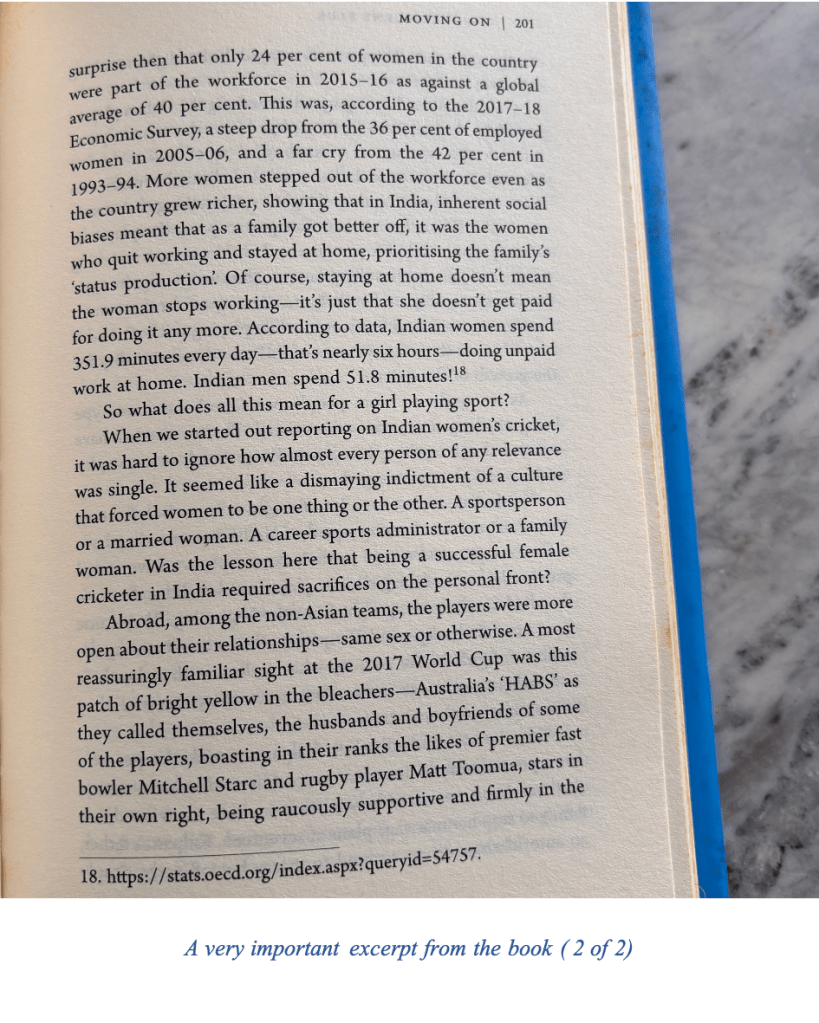

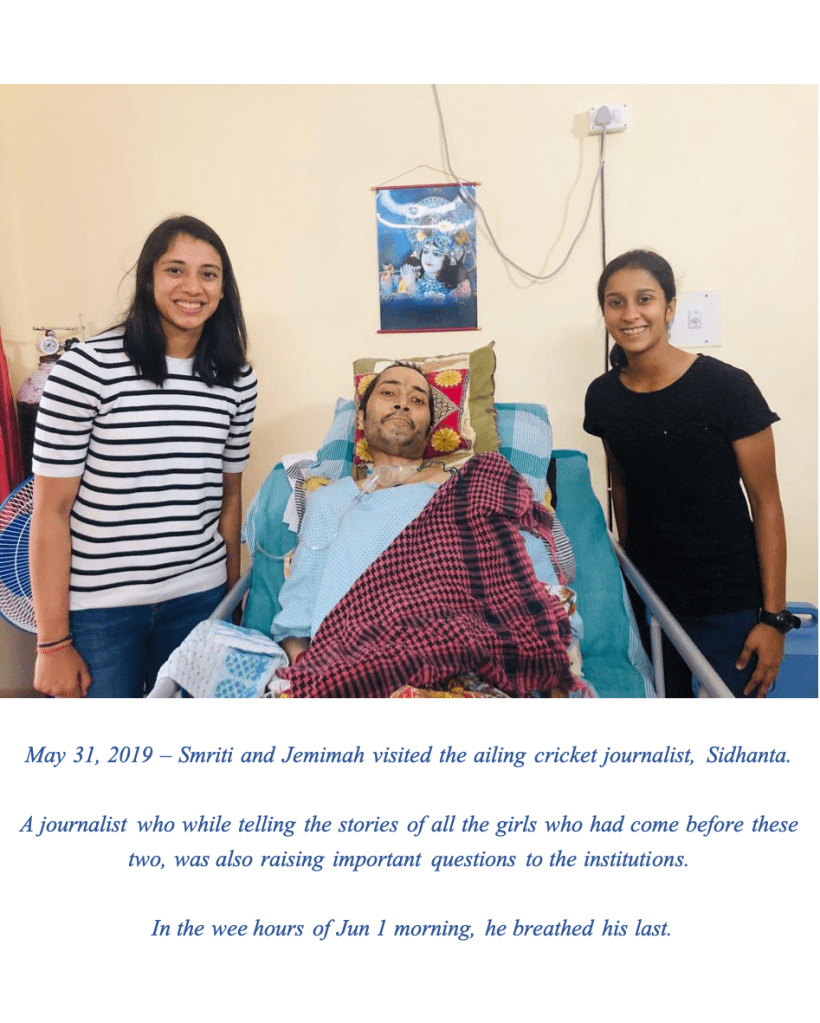

In this context, I remember Sidhanta Patnaik – one of India’s finest cricket journalists. He turned from the lucrative men’s game to chronicle the women who wielded the willow when few others cared. His seminal book with Karunya Keshav, ‘The Fire Burns Blue’, is more than a sports chronicle – it’s an anthropological record of resilience.

Sidhanta succumbed to cancer at 34. My personal loss as a widow pales beside the void his absence leaves in the fight for women in sport. Even as his life ebbed, he worked with Karunya and Snehal Pradhan to set in motion a draft framework on Gender Equality in Sports that continues to guide the policies around women athletes.

His life, brief yet blazing, demanded more from us than applause.

It demanded accountability.

Thus, tomorrow, when India faces South Africa, irrespective of who wins, feminism will take a few steps forward.

~

Sharing a series of photo essays